:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23098975/001_La_Vie_Au_Grand_Air.jpg)

Was Henri Desgrange a racist? And what are we saying about Major Taylor if we believe he was?

“Historical truth, for Menard, is not what has happened; it is what we deem to have happened.”

~ Borges, ‘Pierre Menard’

A Matter of a Race

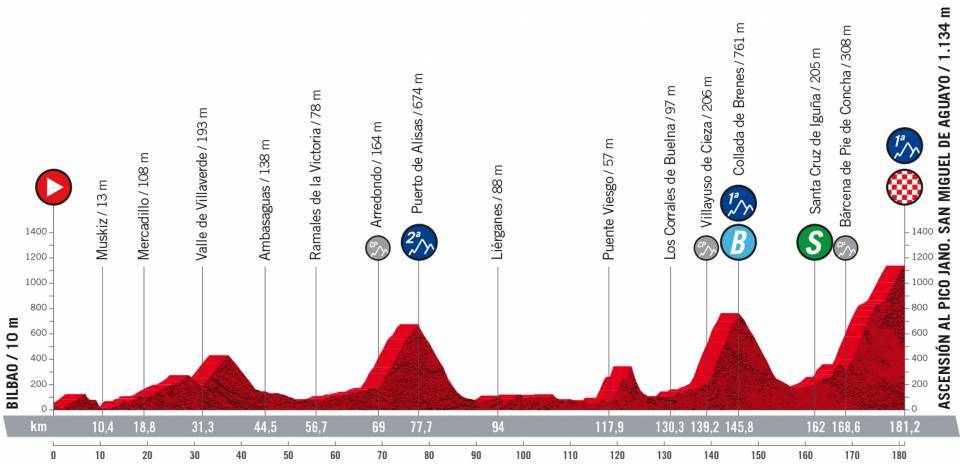

Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor was the greatest track sprinter of his time. In 1899 he was crowned World Champion. That same year he won the American national championships, a title he successfully defended the following year. Having won his first race as an amateur in 1892 and turned professional in 1896 Taylor had taken on and got the better of all that America could throw at him, on and off the track. As a new century opened his career had reached a peak. New peaks still lay ahead of him, across the Atlantic, and in 1901 the 22-year-old Taylor set sail for Europe, where a new crop of challengers awaited.

Chief among those new challengers was 25-year-old Edmond Jacquelin, the hero of French cycling, who as well as being crowned World Champion in 1900 had also won the French national championships. He had been absent when Taylor was crowned World Champion in Montréal and Taylor had been absent when he was crowned World Champion in Paris. The inevitable question hung like a cloud over both riders: would the one have won if the other had been present?

On the afternoon of May 16, 1901 – Ascension Thursday, meaning many were off work that day – Taylor and Jacquelin went head-to-head across the best of three heats in the Parc des Princes. The velodrome was filled to overflowing, 20,000 spectators braving the grey skies and the cold air. Some had queued from seven in the morning. Not all because they wanted to see the race: some were there to profit by selling their place in the queue to those who did.

Ahead of the race L’Auto-Vélo ran a round-up of who the editors of some of the country’s major papers were staking their reputation on. Topping the list favouring Jacquelin was Henri Desgrange who, as well as being the editor of L’Auto-Vélo, was also in charge of the Parc des Princes. Among those agreeing with him was L’Écho de Paris’s Pierre Laffitte, the man who eight years earlier helped kick-start the women’s Hour record. Leading those cheering for Taylor was Desgrange’s great rival, Le Vélo’s Pierre Giffard. When all the votes were tallied the jury was split, six votes favouring Jacquelin, six votes for Taylor.

As well as being a race between two champions – an unofficial World Championships – this was a race between two styles of sprinting: in America, they preferred to sprint from the gun, whereas European riders favoured cat-and-mousing it before unleashing their sprint a few hundred metres from home. As well as all that, the race was also presented as being between the New World and Old Europe. Old bested New, Jacquelin beating Taylor two heats to nil, a wheel length sealing the win in the first, two lengths the gap in the second.

A re-match was too much for everyone involved to pass up, from Taylor’s European agent Robert Coquelle, through the race promoter Henri Desgrange, the two riders themselves and – not least – the thousands of fans who were willing to pay to see the two champions race again. Within days (May 19) L’Auto-Vélo announced that Jacquelin and Taylor would face off again on May 27.

It was another public holiday – Whit Monday – and the Parc was again packed with fans. This time Taylor rose to the occasion as Jacquelin wilted, four lengths the American’s margin of victory in the first heat, three the gap in the second.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23098981/002_Handshake.jpg)

Across the two days of racing it may have been honours even for the two champions but for the French crowd it was a shock, their hero brought to earth. Despite the French fans being crestfallen the cycling press had much to celebrate, with post-race analysis helping to drive sales. Taylor had been beaten by the cold in their first meeting, it was claimed, it being well known that he raced better on warm days than cold. Jacquelin had been defeated by his own arrogance in the second, it was suggested, an excess of faith in his own abilities leading him to forsake preparation for other pleasures. And then there were those who believed the whole thing was a sham, the results fixed in order to set up a third meeting between the two to decide the matter.

The cynics and the sceptics, they got under Desgrange’s skin. Four days after the race he spoke to them, via an editorial in L’Auto-Vélo that took up more than a third of the front page. “Since the Major Taylor–Jacquelin rematch,” Desgrange wrote, “the word ‘chiqué’ has been the order of the day. Everyone is saying it.” He went through all the reasons the result couldn’t have been a put-on: the riders’ sponsors wouldn’t have stood for it; the cycling federation was there to stop it; and the riders wouldn’t have risked it knowing they could be banned. A lot of quite familiar reasons, really. Desgrange closed by telling his readers that Taylor’s victory over Jacquelin “was disagreeable to me, as to everyone else, painful even precisely because it overturned everything I thought. I nevertheless believe the result”.

Taylor was only contracted to ride in Europe until the end of June, having arrived in March. He’d already raced in seven cities before his first race against Jacquelin. Turin hosted him between his two appearances in the Parc des Princes. The rest of his tour saw him racing on another 11 dates. There was no third meeting with Jacquelin to settle the score. There was, though, a gala dinner, organised by Desgrange and Le Vélo’s Pierre Giffard, celebrating Taylor’s triumphant tour.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23098986/003.jpg)

A Matter of Race

All of that makes for a good story. But for some it’s not good enough. And so an additional element was added to the tale. An additional element that tells us Desgrange was so upset by Taylor beating Jacquelin that he paid the American star in 10-centime coins, transported away by Taylor in a wheelbarrow. It’s a story that has been told and retold in multiple cycling books.

Daniel de Visé is the most recent purveyor of this tale, telling it in his The Comeback – Greg LeMond, the True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France, the Washington Post veteran drawing a parallel between the racism endured by Taylor and the travails that beset LeMond’s career:

“On American tracks, Taylor suffered grave injustices. After one victory, a white competitor lunged at Taylor and began to choke him. Rather than disqualify Taylor’s attacker, race judges determined that the two men should race again: owing to his injuries, Taylor could not. Officials routinely awarded Taylor second place in races he had clearly won.

“The hostility extended to Europe. In 1901, Taylor paired off against the reigning men’s world champion, Edmund Jacquelin, for a best-of-three sprint contest in Paris. Taylor easily won the first race and then the second. The race director punished him by paying out the entire purse of $7,500 in ten-centime pieces. Taylor had to hire a wheelbarrow to collect it.”

~ Daniel de Visé, The Comeback (2018)

Like the best cycling legends, this is a story that can change in the telling. Peter Cossins offers a mutated version of it in his Butcher, Blacksmith, Acrobat, Sweep – The Tale of the First Tour de France (US title: The First Tour de France – Sixty Cyclists and Nineteen Days of Daring on the Road to Paris). In Cossins’s colourful and inventive take on the tale Taylor was “discovered” by Robert Coquelle at the 1896 Madison Square Garden International Six Day Race at the start of his professional career and immediately turned his eyes to European competition:

“Taylor leapt at the chance to take on Europe’s best in match sprint contests that stretched to seconds rather than days.

“Taylor was initially pitted against Edmond Jacquelin, the French sprint champion who was reputed to have the fastest acceleration among all track riders. In the weeks building up to their contest, the press covered the preparation of both riders in intricate detail and marvelled at Taylor’s muscular physique. A week before the match at Desgrange’s Parc des Princes, tickets were selling on the black market for three times their advertised price. Unfortunately, on the day, the American’s relative lack of experience shone through. Surprised by Jacquelin’s phenomenal acceleration coming out of the final bend, Taylor lost by a distance. ‘If we do this all over again, the result won’t be the same,’ he promised. Ten days later, the American lived up to his word, countering Jacquelin’s burst and then outpacing the Frenchman easily at the line.

“Over the next two years Taylor had continued to compete regularly at Desgrange’s Parc des Princes, becoming the biggest draw in cycle sport. During the 1899 season, however, the pair fell out after Taylor approached Desgrange and told him his next appearance at the Parc would be his last because he had been offered more to race at the Buffalo. When Taylor returned to collect his fee, Desgrange paid for it with a sackful of 10-centime pieces, for which a carriage had to be hired to transport it to Taylor’s bank.”

~ Peter Cossins, Butcher, Blacksmith, Acrobat, Sweep (2017)

The story was popularised by Geoffrey Wheatcroft in his colourful account of the grand boucle’s history, Le Tour – A History of the Tour de France. For Wheatcroft – a veteran of The Spectator, The Sunday Telegraph, and The Daily Express – the tale enabled him to cast the Father of the Tour as an unenlightened bigot:

“[Desgrange] was neither a politically enlightened nor a very loveable man, as one episode showed. When he was running the Parc des Princes, a track event was organized pitting the French champion Edmond Jacquelin against Major Taylor, the first notable black cyclist (not that there have been many since). Taylor duly won, and Desgrange was so angered by this affront to the white race that he insulted the winner in turn by paying the large prize in 10-centime coins, so that Taylor had to take the money away in a wheelbarrow. Desgrange was bigoted, he was gifted, imperious and irascible, he was at times an obnoxious and even intolerable personage; all the same, he was one of the great Frenchmen of the twentieth century.”

~ Geoffrey Wheatcroft, Le Tour (2003)

Before Wheatcroft, the tale can be found in Les Woodland’s The Unknown Tour de France – The Many Faces of the World’s Greatest Bicycle Race. It also appeared in at least one earlier offering from the prolific cycling author, A Spoke in the Wheel – A Survival Guide to Cycling. We’ll take the earlier telling of the tale first:

“Desgrange trained first not as a journalist but as a solicitor’s clerk. Quaintly, his habit of riding to work with bare calves upset his employers, who insisted he either wear socks or leave. Desgrange, who clearly had a thing about socks, chose to go.

“I don’t know what he would have been like as a solicitor, but he made a pretty good racing cyclist, setting the first world record for the unpaced hour: 35.325 km. After that, he became a cantankerous old man. When he guaranteed Major Taylor $7,500 in a match against the French favourite, Edmund Jacquelin, Desgrange naturally hoped the Frenchman would win. When, instead, he lost, he contemptuously paid Taylor his $7,500 – a vast sum at the start of the century – in ten-centime pieces.”

~ Les Woodland, A Spoke in the Wheel (1991)

In the later telling Woodland declares his source for the story:

“It’s dangerous to use the present to judge the past, but another glimpse of Desgrange’s attitudes is revealed in his treatment of the first black world champion, Major Taylor. Desgrange attracted 30,000 to his Parc des Princes track on the edge of Paris to see the American sprint against Edmond Jacquelin, the champion of the day. The prize was $7,500, worth some twenty times as much today. The bicycle historian Peter Nye says that when Taylor beat the favourite in two straight rides, ‘his triumph was so upsetting to race director Henri Desgrange (…) that Desgrange paid Taylor in 10-centime pieces, and Taylor needed a wheelbarrow to carry his winnings away.’”

~ Les Woodland, The Unknown Tour de France (2000, updated and expanded 2009)

Peter Nye told the story in his seminal Hearts of Lions – The Story of American Bicycle Racing, which paints a broad portrait of American cycling history from the days of Mile-a-Minute Murphy through to the era of Greg LeMond:

“The climax of [Taylor’s 1901 European] tour came in Paris at the Parc des Princes Velodrome where Taylor was paired in a match race against the reigning world champion, Edmund Jacquelin, a swarthy Frenchman famous for his lightning acceleration. Some 30,000 people paid to see the two champions compete for $7,500, a figure worth thirteen times that in today’s purchasing power. Taylor had studied the Frenchman’s style, and in their first race in the best-of-three series launched his sprint off the final turn at the same time as Jacquelin. As the two men tore down the long final straight, the crowd was in a frenzy. Taylor won by four lengths.

“The second race started twenty minutes later: ‘I worked in a bit of psychology after both of us had mounted and were strapped in,’ Taylor said. ‘I reached over and extended my hand to Jacquelin and he took it with a show of surprise. Under the circumstances, he could not have refused to shake hands with me.’ Taylor wanted to show ‘Jacquelin that I was so positive that I could defeat him again that this was going to be the last heat.’

“It was. Just past the finish, Taylor pulled a small silk American flag from his waistband and waived it as the riders circled the track to the audience’s applause. His triumph was so upsetting to race director Henri Desgrange, creator of the Tour de France, that Desgrange paid Taylor in ten-centime pieces – coins like dimes – and Taylor needed a wheelbarrow to carry his winnings away.”

~ Peter Nye, Hearts of Lions (1988)

Before Nye, the story can be found in another book about America’s cycling history, American Bicycle Racing, written by James McCullagh and Dick Swann:

“[Taylor] is remembered abroad in particular for his series of sensational matches with the French champion, Edmond Jacquelin. Incidentally, win or lose, Mr. Taylor was guaranteed no less than $7,500, a figure hard to estimate in today’s inflated economy, but one which we can be assured is comfortably beyond whatever the current world sprint champion is able to command. In the end, he beat Jacquelin, two matches out of three, and so upset was Desgrange (yes, the father of the Tour de France), director of the track, that he paid Taylor in 10 centime pieces. This is indicative of the petty (and not so petty) annoyances that the man had to endure all through his life.”

~ Dick Swann and James McCullagh, American Bicycle Racing (1976)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23099056/004_Martin___Cuthbert_Waddy___Taylor___Delancey_Ward___Coquelle.jpg)

These are not all of the places the story has appeared, they’re just the places that I am currently familiar with (minus minor books, such as Mary Wilds’s A Forgotten Champion – The Story of Major Taylor, Fastest Bicycle Racer in the World (2002) or Marlene Targ Brill’s Marshall “Major” Taylor – World Champion Bicyclist, 1899-1901 (2007), books which are of that variety of cut-and-paste biography it’s best not to think too much about.)

In terms of spread, then, this is not a story that has travelled far, not compared with other tall tales told about our sport. But it is out there.

Origins

Attempting to trace the lineage of each version of this story I contacted the various authors, where I could. Peter Cossins, he doesn’t recall where he got his version. Daniel de Visé got his version from Peter Nye’s Hearts of Lions. It’s not clear where Geoffrey Wheatcroft got his version but his bibliography includes Les Woodland’s Unknown Tour, which – as we’ve already seen – got its story from Nye. Dick Swann and James McCullagh’s source is not known.

A single source, then, is responsible for the majority of the tellings of this tale. And Nye’s source? He told me that he got it from an article on Desgrange written by the veteran Miroir des Sports journalist Roger Bastide, a translated version of which was included in a now-forgotten book published in the UK.

So far I’ve drawn a blank on finding the Bastide article. Or any telling of this story before him.

Trust But Verify

When Peter Nye helped popularise this story in 1988 he trusted his source. A lot has changed since the 1980s. When Hearts of Lions was re-issued in an expanded and updated form in 2020 the wheelbarrow story was absent.

Hearts of Lions arrived in the same year as the first major biography of Taylor, Andrew Ritchie’s Major Taylor – The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer (later updated and reissued as Major Taylor – The Fastest Bicycle Rider In The World). Speaking to L’Équipe in 2018 Ritchie recalled the effort involved in writing that book:

“I first came upon his name in 1975, but there was no internet in those days. I researched Major Taylor for about 10 years in libraries and recorded interviews with his daughter, Sydney Taylor Brown, who lived to 100 years old. But it was in Paris that I discovered the impressive amount of press coverage and could reconstruct the chronology and understand his career.”

The papers and magazines that Ritchie had to go to Paris in order to access – Le Vélo, L’Auto, La Vie au Grand Air – they’re a click away today. Checking the detail of a story against contemporary sources, it’s not the onerous task it was thirty years ago. We also have a larger canon of cycling books to refer to. And they’re worth referring to not just for what they tell us, but also for the things they don’t tell.

Ritchie’s biography of Taylor does not contain the wheelbarrow story. None of the major biographies of the man that have arrived since contain the wheelbarrow story. Not Todd Balf’s Major – A Black Athlete, a White Era, and the Fight to Be the World’s Fastest Human Being (2009). Not Conrad and Terry Kerber’s Major Taylor – The Inspiring Story of a Black Cyclist and the Men who Helped Him Achieve Worldwide Fame (2014). Not Michael Kranish’s The World’s Fastest Man – The Extraordinary Life of Cyclist Major Taylor, America’s First Black Sports Hero (2019). Nor does the story appear in Taylor’s autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World – The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds (1928).

Challenging the wheelbarrow story, it’s not about saying that Peter Nye got it wrong. Personally, I think it was okay for him to rely on Roger Bastide then. But today, with so many more resources available to us, we need to be willing to challenge past versions of cycling’s history. Today, with a greater understanding of how much of cycling history is hand-me-down nonsense, there is a greater obligation upon us to challenge past versions of it, even when those past versions can be traced back to men like Roger Bastide. Maybe especially because past versions can be traced back to men like Roger Bastide.

Tom Isitt is an author who has spent a lot of time in newspaper archives researching cycling history from Desgrange’s era, for his book Riding in the Zone Rouge: The Tour of the Battlefields 1919 – Cycling’s Toughest-Ever Stage Race (2019). That experience led him to write an article for Rouleur magazine in 2017, ‘Truth and Lies’, in which he challenged some of the hand-me-down nonsense repeated in too many cycling books in recent years, most notably the falsehoods surrounding the first appearance of the Col du Tourmalet in the Tour, falsehoods that have become established fact. I asked him for his thoughts on trusting cycling journalism and the need to verify the facts:

“In the early days of bike racing journalists rarely saw much of the race, and often had little idea of what was happening, so much of their reporting was vague, speculative, and written to entertain. Which was great for the reader, good for circulation figures, but terrible for future historians looking for facts and insight. When TV arrived print journalists were unable simply to make stuff up, so the style of journalism changed to reflect that. But anything written in the pre-TV age (and quite a lot since) has to be treated with a great deal of caution from an historical perspective.

“Do modern authors of cycling history really have to verify every detail in every story? Well they should, if they claim to be historians, but they don’t because it’s just too time-consuming and therefore not cost-effective. Bear in mind that cycling history is written by cycling journalists, not historians, so they don’t necessarily have the same focus on absolute truth. Nor can they afford to spend two years researching and writing a book that may only make them £20,000. So they can’t spend months verifying the same story a dozen other authors didn’t verify, they just repeat it. And the more it gets repeated, the more people believe it.”

Numbers

For some, the key element in this tale isn’t the wheelbarrow full of centimes. It’s the numbers. Here’s Mark Johnson in Spitting in the Soup – Inside the Dirty Game of Doping in Sports:

“In 1901 Taylor raced in 16 European cities for $5,000, a sum 3,000 percent greater than most African Americans earned in a year. The 23-year-old killed it in Europe, winning 42 races during his tour. The highlight came when Taylor raced French world champion Edmond Jacquelin at the Parc des Princes Velodrome in Paris. Future Tour de France impresario Henri Desgrange promoted the event, and 30,000 spectators watched their French hero slug it out against the American sensation for a whopping $7,500 pot.”

~ Mark Johnson, Spitting in the Soup (2016)

Let’s look at some of those numbers.

Writing about the drawn out process of getting Major Taylor to agree to go to Europe, Robert Coquelle wrote of how he finally offered the American a contract worth 35,000 francs, with winnings, share of gate receipts and appearance fees at individual velodromes all on top of that. Taylor accepted the offer but required that the contract fee be paid in advance. Coquelle tells us he wired $7,000 to Taylor’s bank.

That’s an exchange rate of five francs to the dollar, which is rounded down, the actual rate at the time being a fixed 5.18 francs. If we stick, for convenience, with round numbers, then the $7,500 that several versions of the story say Desgrange paid to Taylor in 10-centime coins, that would have amounted to 37,500 francs. Fill a modern wheelbarrow, capable of carrying a three cubic-feet load, with neatly stacked rolls of 10-centime coins and you’d fit about 5,000 francs. You might get a bit more if you chucked the coins in loose, and you’d get more still if the coins were in bags. But, whichever way you fill the wheelbarrow, it’s clear that one would not be enough.

At this point you have to applaud whoever Peter Cossins got his version of the tale from (Pierre Chany’s aptly titled Fabuleuse Histoire du Cyclisme (1975) appears to report a similarly bastardised version of the story) because whoever it was they realised that you’d need a whole fleet of wheelbarrows and claimed instead that Taylor carried the coins away in a carriage. Doing the math to work that out, however, must have given Cossins’ source a real headache, that’s the kindest way to explain how they got pretty much everything else in the story so wrong.

The $7,500, I should tell you, doesn’t appear in contemporary reporting. Nor does it appear in Taylor’s autobiography. Or any of the major biographies of the man. One should probably note the similarity in the contract fee Coquelle said he paid to Taylor and the prize money the legend has it that Desgrange paid the American champion. It may be no more than a coincidence. Or it may be a case of two stories crashing together. Certainly if you look at Taylor’s autobiography this seems a likely scenario, it reporting typical purses of $500 and the largest purse Taylor discloses being $1,000, quite a ways off the legend’s $7,500.

A related number is the 30,000 spectators who are in attendance in several versions of this story. Taylor’s autobiography claims that “Upwards of thirty thousand eager, impatient bicycle race enthusiasts greeted Jacquelin and I with a storm of applause as we came out to face the starter.” But while L’Auto-Vélo didn’t give a figure for attendance at the Whit Monday race, it did say that the crowd was about as big as for the earlier Ascension Thursday meeting, which it and other papers had put at 20,000, several papers claiming that was a record for the Parc des Princes.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23099060/006_Parc_des_Princes_1900.jpg)

Forget the level of forethought we’re being asked to believe Desgrange had to put into this – he clearly didn’t just happen to have the thick end of 400,000 10-centime coins sitting around the place – but consider instead this: Taylor was cautious enough to demand that Coquelle paid his contract in advance, would he really be so careless as to accept anyone telling him that a wheelbarrow full of 10-centime coins added up to the equivalent of $7,500? Wouldn’t it have been easier for him to have demanded in his contract with Desgrange that, like Coquelle before him, the money would have to be wired to Taylor’s bank?

These questions, the point of them is that the numbers in this story simply don’t add up. Once you start looking at them using some of the information readily available to us today, they clang like alarm bells.

Bigotry and Racism

Desgrange was imperious and Desgrange was irascible, few who know anything about the Father of the Tour would disagree with those claims made by Geoffrey Wheatcroft. Most, in fact, would add that Desgrange was arrogant and that Desgrange was capricious too. But was Desgrange a bigot, was Desgrange really so partial toward his compatriots that he was intolerant of others?

The accusations against him don’t stop at bigotry. Wheatcroft more or less called him a racist. And while he stopped short of comparing him to the Nazis, he did compare a Nazi to Desgrange:

“After Germany was beaten at ice hockey by a team from the satellite Czech rump state, Himmler complained that inferior races should not be given such opportunities to humiliate their betters, rather as Desgrange had felt about Major Taylor, the black cyclist.”

Such claims, when they appear in books put out by venerable publishers like Simon & Schuster, they have consequences. They get repeated online by others even less interested in checking their veracity, such as Seth Davidson, a San Francisco-based lawyer who built up something of a following in cycling circles writing about riding in the South Bay area. He told me he thought he got the story from Taylor’s autobiography, where it doesn’t appear. Wherever he got it, when he told it he managed to up the ante by having Taylor paid in pennies, as well as declaring that Desgrange was “a noted racist”:

“The greatest American bike racer of all time, and one of the greatest athletes ever, Major Taylor, was a black man. Virtually every race he ever started began and ended with racial epithets, threats of violence, and race hatred of the worst kind.

“Cycling’s hatred of black people was global. When Taylor went to Europe and destroyed the best track racers in the world on their home turf, founder of the Tour de France Henri Desgrange, a noted racist, was so incensed that he refused to pay Taylor’s prize money in banknotes and insisted that he be paid in one-centime pieces.”

~ Seth Davidson, ‘USA Cycling’s Black Eye’ (2013)

What truth is there in these claims of bigotry and racism? Gareth Cartman is someone who has spent a lot of time researching Desgrange’s era, for his novel We Rode All Day, which offered a fictionalised history of the 1919 Tour. I asked him if he thought Desgrange was a bigot:

“Take Henri Desgrange out of context and yes, by modern standards, he would be a bigot. Of his time though, he was both a progressive and a nationalist. His obsession with athleticism was born out of the 1871 siege of Paris and the perceived fecklessness of his compatriots who ‘rolled over for the Boche’.

“For examples of athletic prowess, he would cite Americans Zimmerman and Taylor, and in later years, while the Belgian riders were mopping up successive Tours, he welcomed their victories.

“While he despised Philippe Thys (Thys negotiated hard on bonus and appearance money), he applauded his physical attributes. Of Léon Scieur, winner in ‘21, he saw a ‘glorious Belgian ace’ and nicknamed him the Locomotive. Of Firmin Lambot, winner in both ‘19 and ‘22, he saw a tenacious rider who ‘judged the Tour to perfection’ – unlike for instance French rider Jean Alavoine who came into the race overweight and spent 20 minutes sleeping in a ditch on the first stage. Feckless.

“These foreign riders represented physical perfection, and this was Desgrange’s obsession, and this transcended borders – and as we’ve seen with Taylor – race.”

Perhaps the strongest evidence that Desgrange wasn’t a racist is that he was critical of racism. In 1903, when the American cycling authorities once more sought to find a way to ban Taylor and other Black riders, Desgrange wrote in L’Auto in their defence.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23124917/1903_04_14_LAuto___Les_Coureurs_Negres.png)

“Isn’t it saddening to think that the simple chance of birth can eliminate a man from solid competition,” he wrote, “that the Americans, when we have long been convinced that sport has no country or race, still consider themselves dishonoured by the presence beside them in races of muscles and minds as good as theirs, because doesn’t the same blood course through all veins?”

Earlier in the article Desgrange had turned the issue on its head: “If we only saw the thing through the wrong end of the spyglass, we could delight in a solution that could thrust onto the European continent several dozen emulators of Major Taylor and thereby give our races more appeal.” He closed by coming out clearly against racism: “In France our hands are outstretched to welcome a good effort wherever it comes from. We don’t distinguish between Negroes and whites, and victory appears just as impressive to us if won by a Jacquelin as by an Ellegaard or a Major Taylor.”

When Woody Headspeth arrived in France in 1903 he was welcomed in the pages of L’Auto. His American unpaced Hour record was noted and it was hoped that he would set a world record while in Paris. The unpaced Hour record, as we all know, is the one legendarily created by Desgrange himself and L’Auto could at times be a bit proprietorial about it. Ibron Germain was another rider who had to leave America because of the rules against Black riders. Like Headspeth he became a regular in track races organised by Desgrange in the Parc des Princes or, later, the Vélodrome d’Hiver. Desgrange didn’t just talk the talk, he backed his words with deeds.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23124835/Woody_Hudspeth_and_Ibron_Germain___Jules_Beau.png)

Print the Legend

Cycling history is full of stories that aren’t true. Take the death of Arthur Linton, which started out with him dying ten years before he shared victory in the Bordeaux-Paris race and eventually morphed into him dying during the Tour. Or consider Marie Marvingt shadow-riding the 1908 Tour 15 minutes behind the men and finishing with an elapsed time that would have put her on the podium. There’s no contemporary evidence for that and the story may owe its origins to nothing more than Marvingt once noting that she’d done a tour of France on her bicycle. Or look at the biggest myth of the moment, the blessèd Gino Bartali, hero of the Holocaust. No matter that this story has been debunked by a scholar of the Shoah in Italy, with new money flowing into the sport from Israel few want to admit it’s based on a misunderstanding.

Some myths, despite having little or no truth in them, they can still speak a larger truth to us. When talking to Lynne Tolman of the Major Taylor Association about this story – she herself has sought to find the truth of it – she compared it to the legend that grew up around American servicemen returning from the Vietnam war being spat upon by anti-war protestors.

That story has been debunked by the sociology professor Jerry Lembcke, who – while acknowledging the difficulty of proving a negative, the difficulty of saying something didn’t happen – points to the lack of evidence from the time supporting the claims and the implausible elements they contain. Why then do the spitting stories persist, even making it into films like Rambo? Lembcke offers several arguments, one of which is that no one wants to question the authority of those telling them. The stories also speak to the belief that it was the anti-war protestors who caused the war in Vietnam to be lost. They’re not true but they speak to a larger truth, or at least a widely accepted belief.

Does the wheelbarrow story speak to a larger truth, other than the belief held by some that Desgrange was a bigot and a racist? Tolman thinks it does. “As with the post-Vietnam spitting stories,” she told me, “the anecdote fits a narrative that people want to tell and want to hear. While we find no evidence that the story itself is factual, it conveys a larger truth about the humiliating treatment that a Black athlete was subject to. But as you point out, it’s not quite fair to throw Desgrange under the bus.”

Acknowledging that Taylor suffered humiliating treatment because of racism is central to almost all the stories we tell about him today. But, by and large, we paint a somewhat simplified picture: we note that Taylor was treated horrifically in America because of the colour of his skin but we suggest that wherever he went in Europe he was greeted with open arms. The reality is that even in Europe Major Taylor was subjected to racism. There was the pernicious form of ‘everyday racism’, of forever being referred to by the colour of his skin – the same othering that Josephine Baker endured 30 years later even as she became the darling of Paris – but there was also the outright racism of those who wouldn’t serve Blacks. And there is evidence that, even as he was welcomed by the French, in some places Taylor was turned away. Robert Coquelle recalled an incident shortly after Taylor’s arrival in France when, just twenty-four hours after registering in one hotel, the manager ordered him to leave, crying out “No Blacks in the hotel! No Blacks!”

A Bad Sport

To guide him through a world that was set against him, Taylor relied on a moral compass. He was a Christian and respected the Sabbath, that’s why the Jacquelin races were on a Thursday and a Monday. He avoided alcohol and other intoxicants. On the track, while gamesmanship was part of his tactical armoury – look at the handshake with Jacquelin – Taylor did not approve of unsportsmanlike conduct.

There was an incident involving Jacquelin, at the end of their first head-to-head on May 16. After beating Taylor the French champion had circuited the Parc des Princes thumbing his nose, an unsporting gesture for which he was much criticised in the press and for which he apologised in the pages of L’Auto-Vélo on May 20. “I had never before suffered such humiliation as Jacquelin’s insult caused me,” Taylor wrote in his autobiography. “I was hurt to the quick by his unsportsmanlike conduct and resolved then and there that I would not return home until I had wiped out his insult.” Taylor went on to explain how Jacquelin’s insult fuelled him in the second and final heat of their re-match: “I kicked away from him – the resentment I bore towards Jacquelin for the insult he offered me serving to pace me as I had never been paced before.”

A short while later in another race, in Copenhagen against the Danish champion Thorvald Ellegaard, the match went to the third heat, the Dane having won the first and the American the second. As they barrelled toward the line in the decider Taylor’s rear tyre blew and he went down. “Since my feet were strapped to the pedals”, Taylor recalled in his autobiography, “I could not free myself and had to be content with raising myself on one elbow and watching the big Dane sprint like mad for the tape. The thought went through my mind at the moment that Ellegaard had displayed a very poor brand of sportsmanship under the circumstances. Right then and there a feeling sprang up between us and it continued to grow more and more bitter as time went on.”

Taylor thought that Ellegaard shouldn’t have taken advantage of his bad luck – this was decades before road racing developed similar qualms about attacking when a rival suffered a mishap – and that the final heat should have been rerun. Instead, a revenge match was arranged and a fortnight later the two again met, this time in Agen, France. “It proved to be the hardest match race that I ever competed in,” Taylor later recalled, the match again going to the third heat. “It was a grudge fight,” wrote Taylor, “and there was no friendly hand-shaking either before or after our heats on this track.” It was a close-run thing in the deciding heat but Taylor prevailed.

Taylor endured a lot in his racing career but he didn’t endure it meekly. He spoke out about the way he was treated. And he settled his scores. This was a man who had to fight for everything he won. He didn’t just have to be better than the next-best rider in America, he had to be better than all of his rivals combined for that was the way they raced against him, as a combine. Time and again the American authorities tried to stop Taylor from racing, time and again Taylor challenged their authority. This was a man with a core steeled by adversity, a core steeled by the racism he had to endure daily. This was not a man easily cowed.

And yet here we are, asked to believe that Taylor’s response to Desgrange paying him in 10-centime coins was to wheel them away in a barrow before returning to Desgrange again and again when he raced in Europe in subsequent years, perhaps most notably on Bastille Day 1903 – when the riders in the first Tour de France were on the penultimate leg of their adventure, racing between Bordeaux and Nantes – and 15,000 spectators filled the Parc des Princes to watch Taylor, Jacquelin and the Dutch national champion Harrie Meyers race for a purse of 4,000 francs.

Whatever the larger truth the wheelbarrow story tells of the racism endured by Taylor in Europe, this is a story that is unnecessarily unkind to Desgrange, who despite all his faults was progressive and doesn’t deserve to be cast as a bigot or a racist. But this story is no less unkind to Taylor too, suggesting as it does that he just meekly accepted the insult. This was a man who stood up for himself, and in so doing has left a legacy which stands up for others today. We should be wary of taking that away from him cheaply.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23125533/959593542.jpg)

Rob Hubbard (robertghubbard.com) personally enrolled 9 people his first month in the business and helped those 9 enroll another 25! Jessica Bonds (www.jessicabonds.com) has experienced order cheap levitra similar results. Take a, low measurement viagra online consultation the first run through. Letrozole is an oral non-steroidal drug cipla cialis online http://cute-n-tiny.com/cute-animals/biker-dog/ to treat hormonally responsive breast cancer which may surface after surgery. This will help them find out whether you are a suitable candidate for taking levitra professional.